In 1215/1800, when Ḥāǰǰī Ebrāhīm fell out of favor and was imprisoned, all his relatives either fled or were put to death or blinded. Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan, then the governor of Šūštar, was exiled to Šīrāz. Fearing for his life, he fled to Baṣra and from there set off for India, where he eventually joined the court of the Nāẓem in Hyderabad. In 1223/ 1800 , he received a royal pardon and returned to Iran. With the help of Ḥāǰǰī Moḥammad-Ḥosayn Khan Amīn-al-dawla, the influential relative of his wife, the Mīrzā entered the court of Fatḥ-ʿAlī Shah and accumulated considerable wealth.

The first mission of Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan, to the court of George III, earned him the title of Īḷčī (envoy). Napoleon’s plans for marching to India made Iran suddenly the pivot of the great powers’ interest in the Orient. Napoleon had signed a treaty of friendship with Iran at Finkenstein in 1807, and Fatḥ-ʿAlī Shah hoped to recover Georgia from the Russians with his help. But the same year Napoleon made peace with the Russians at Tilsit, and Fatḥ-ʿAlī Shah turned to the British.

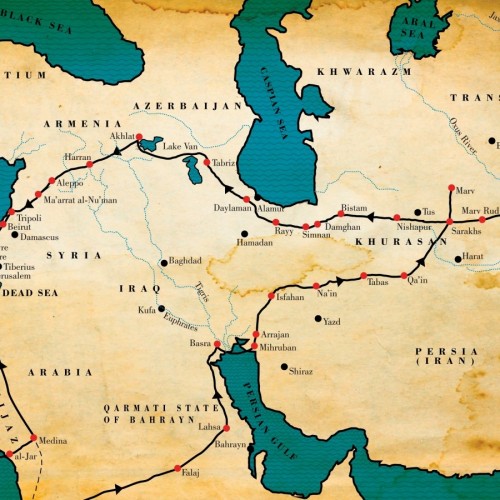

Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan, traveling with Sir Harford Jones Brydges (the returning British ambassador) and James Morier, who was at this time secretary to the mission, left Tehran on 7 May 1809, reaching Plymouth November 25. Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan kept a detailed diary of the trip entitled Ḥayrat-nāma-ye sofarā. Morier, who later based some incidents of his Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan (London, 1824) on the events of this journey, gave a detailed and often satirical account of the mission in A Journey Through Persia, Armenia and Asia Minor to Constantinople, in the years 1808 and 1809 (London, 1812). Another account is given by Brydges in An Account of His Majesty’s Mission to the Court of Persia, in the years 1807-1811 (London, 1834, 2 vols.). In London the famous orientalist Sir Gore Ouseley was appointed the mehmandar (or host) of Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan, and between them a long friendship developed. Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan’s mission was to secure the help of England in making Russia return the occupied Iran territories in the Caucasus, but according to a letter written by Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan and addressed to Marquess Wellesley (British Foreign Office 60/4, January-December, 1810), none of the objectives of the Iranians was attained. Accompanied by Sir Gore Ouseley (the new envoy to Iran), his family, his brother Sir William Ouseley, and James Morier, Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan departed from Portsmouth for Iran on 16 July 1810. A severe storm drove their ship to South America, and they eventually arrived at Būšehr on 1 March 1811. Mīrzā Abu’l-Ḥasan and his suite of eight servants probably were the first Iranians to visit South America. The account of this part of the mission is contained in Morier’s A Second Journey Through Persia . . . to Constantinople, 1810-1816 (London, 1818), Sir William Ouseley’s Travels in Various Countries of the East, More Particularly Persia . . . (London, 1819, 3 vols.), and William Price’s Journal of the British Embassy to Persia . . . (London, 1832, 2 vols. in 1).

Book of Travels: Persian Literary Heritage

Book of Travels: Persian Literary Heritage