One reads, for example, of excursions organised by the shah with his estimated eight hundred ladies of the harem. At the beginning of his reign these took place once or twice a week, bringing the activities of whole areas of the city to a standstill, because all males, even boys and old men, were banned under penalty of death from the streets through which the royal procession was due to pass. The discrepancy between this outer veneer and the tawdry reality underneath becomes positively grotesque when one finds others, no doubt in all sincerity, reporting that the people revered this ruler and that life during his reign was not at all bad for them.

As a matter of fact, dissatisfaction with conditions in the country did not find expression in uprisings of any significance. How is one to explain this? Undoubtedly the Persian government's aggressive policy of centralisation since the reign of 'Abbas I had in the meantime borne fruit. Quasi-autonomous provincial administrations had been systematically eradicated. At the same time, those elements most likely to constitute a threat to the shah, especially the Qizilbash and their leaders, had been divested of power and ultimately suppressed. However, this is not of itself an adequate explanation.

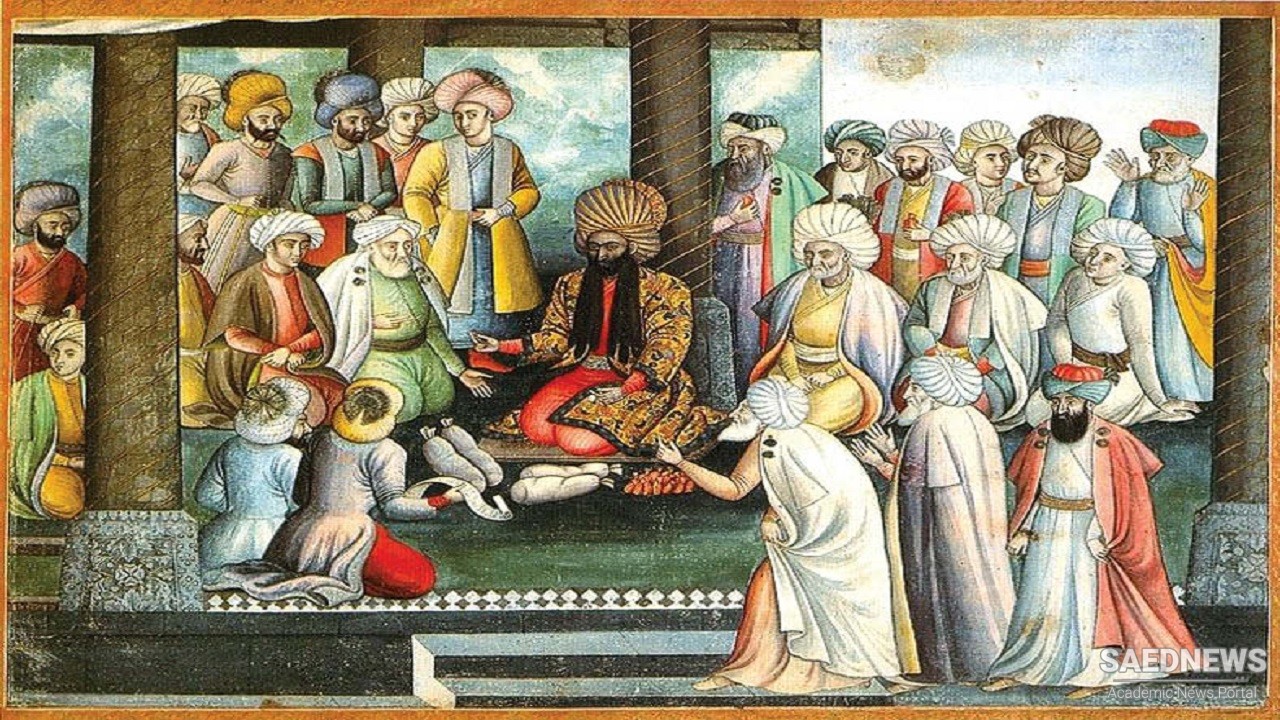

It is doubtless also significant that, according to Malcolm, no events whatsoever of major importance occurred during the reign of Sulaiman. But what decisively influenced public verdict on the shah was probably the fact that he did not involve the country in war. His apathetic and nonchalant attitudes may well have been construed as a love of peace. In the judgement of the masses, reports of the dignified bearing and the external appearance of this blonde, blue-eyed man of great physical strength4 are likely to have outweighed any evidence of lack of initiative.

It is true that in the sphere of foreign policy Sulaiman avoided doing anything that might lead him into difficulties. Although the Ottomans, owing to wars with Austria, Poland and Venice, would scarcely have been capable of action on any large scale in the eastern parts of their empire, he steadfastly refused to violate the peace treaty which his grandfather had made with the Porte in 1049/1639; tn*s despite, for instance, repeated offers from Mesopotamia (1684, 1685) and from Basra (1690) to re-establish Persian suzerainty there. In addition, he allowed the Dutch East India Company to establish a base on the island of Kishm in the Persian Gulf. Similarly he shunned conflict with Russia when the Cossacks, in the course of their increasingly frequent incursions on the southern coast of the Caspian Sea after 1662, requested on more than one occasion that they might be placed under Persian suzerainty.

Disintegrated Rulership

Disintegrated Rulership