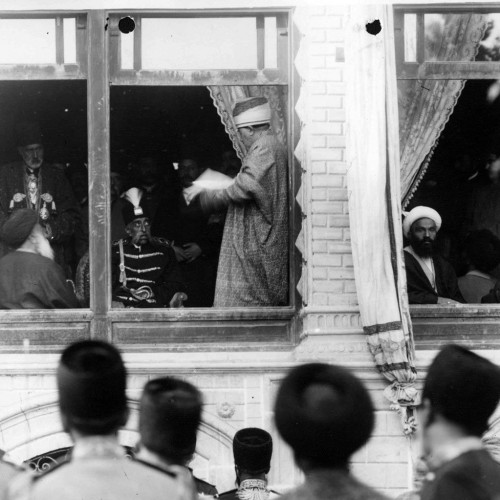

The palpable allure of firearms in the photographs of the time signified a new mood of defiance, as if weapons empowered ordinary citizens to resist the coercive state and its agents. The photographs, and especially portrayals of the two leaders of the resistance, widely circulated in the form of postcards. They were meant to build up confidence among the people of Azarbaijan and the rest of the country, and soon after to celebrate their victory. And in that, images of the photogenic Sattar proved particularly effective.

The sense of camaraderie was also evident in the way that Georgian and Armenian as well as Baku Muslim volunteers were incorporated into the Tabriz resistance. Recruited by the Baku Social Democratic Party and other radical organizations, these militia forces brought with them superior techniques of urban warfare and a new revolutionary spirit, which helped transform the Tabriz resistance into a national struggle. The Georgian detachment of one hundred volunteers was skilled in urban warfare and the use of explosives, whereas the Armenian Dashnaktsutyun nationalists were experienced in tactical warfare. Baku socialists, in contrast, were crucial in supplying ammunition and new weaponry, and in transferring funds and crossing government lines, at great risk and loss of life.

Of the handful of Westerners who observed the Tabriz resistance, one decided to join in. Howard Baskerville, a twenty-four year-old Nebraskan and recent graduate of Princeton who was serving as a teacher of English and science at the American Presbyterian Memorial Boys School in Tabriz, was a passionate volunteer. Moved by the courage and sacrifice of the Tabriz fighters, and especially the assassination of one of his Iranian colleagues, and despite the wishes of the American consulate, he resigned from his post and embarked on training an elite force. At one time, the group totaled nearly 150 volunteers from among the city’s affluent youth. Relying on his own rudimentary military training, Baskerville and his “rescue squad” hoped to break the government siege of the Fada’i neighborhoods by a surprise attack on the Cossack contingent that was camping at the edge of the city. Despite Sattar’s reluctance, and lacking the support of his own volunteers, Baskerville decided to charge, only to be shot point-blank. His grand funeral was a tribute more to his heroism than his good judgment. It was also the height of an ecumenical camaraderie that broke through ethnicity, religion, and nationality.

Baskerville’s death occurred at the height of the Tabriz resistance, in April 1909. Mustering all its forces, the Tehran government eventually and with great difficulty blockaded all supply routes to Tabriz in hopes of starving the city into surrender. The grievous siege of Tabriz between January and April, which caused widespread shortages, had the potential to break the resisting constitutionalists. Although fighting forces in Rasht and Isfahan, by then called the nationalists (melliyun), were acting in greater accord with Tabriz, and although the Tehran regime appeared pliant—issuing a royal decree that promised restoration of the constitutional regime—the Russian legation in Tehran, conveying St. Petersburg’s wishes, was not willing to compromise. The loss of Tabriz would be a serious blow to Russian prestige, not only because the tsarist government was heavily invested in Mohammad ‘Ali Shah’s survival but also because a constitutionalist victory could rekindle a revolutionary spirit in the Caucasus. All the more, even the liberal press in St. Petersburg praised the Tabriz fighters and was critical of Tehran’s callous despotism.

Securing the safety of Russian nationals offered the needed pretext for Russian troops to intervene in accordance with the Anglo-Russian agreement of 1907 and with the tacit approval of London. They crossed the Iranian border and by the end of April 1909 marched into Tabriz. Their arrival, the first since the 1827 occupation of the city after Iran’s defeat in the war with Russia, aroused mixed feelings among the inhabitants. It opened the supply lines, relieving starvation, and facilitated the resumption of trade. The de facto cease-fire brought calm and security, which had been missing since the start of the fighting nearly a year before. Yet occupation was seen as a major setback for the national struggle. Though government troops lifted the siege, retreated to their camps, or withdrew completely from around the city, the prospects of the Russian military presence were ominous enough for Mohammad ‘Ali Shah.

Iran's Nascent Constitution, Its Enemies and the Future of Rule of Law

Iran's Nascent Constitution, Its Enemies and the Future of Rule of Law