Meanwhile, similar formations were developed in other regions as anjumans were created in Tehran, Gilan, Khorasan, and Esfahan provinces. The peasants in Gilan, who joined the volunteer forces and became active defenders of the nationalist movement, gained a reputation as superior guerrilla fighters. In one encounter with the Gilan guerrillas, an army report noted, “We saw no one, but a hundred bullets rained on us.” The Bakhtiari and other tribesmen who fought with the mujahedin, meanwhile, numbered several thousand and had the same qualities and skills as shown by the tribal levies used by the Qajar armed force. Although they are unlikely to have greatly enhanced the irregulars’ capabilities, some former Qajar soldiers joined with the mujahedin.

The Qajars paid for their neglect of the army during the crisis. At the height of the protests, the commander of several of the regular army regiments garrisoned in Tehran announced that his troops would not fight against the people. In other cities Qajar soldiers either refused to fi re on the protestors or joined them. In a lett er to the Shah titled “The Patriot’s Cry from the Heart,” a leading senior cleric in the Constitutionalist movement appealed on behalf of Iranian soldiers, writing that the sarbaz “is deprived of his meager rations and wages and mostly earns his sustenance by coolie labor.” He claimed that many soldiers perished from hunger every day, stating, “No worse defect than this can be imagined for a kingdom.” Only after the government increased and distributed their pay were soldiers in Tehran willing to perform some duties, such as clearing streets and forcing shops to open.

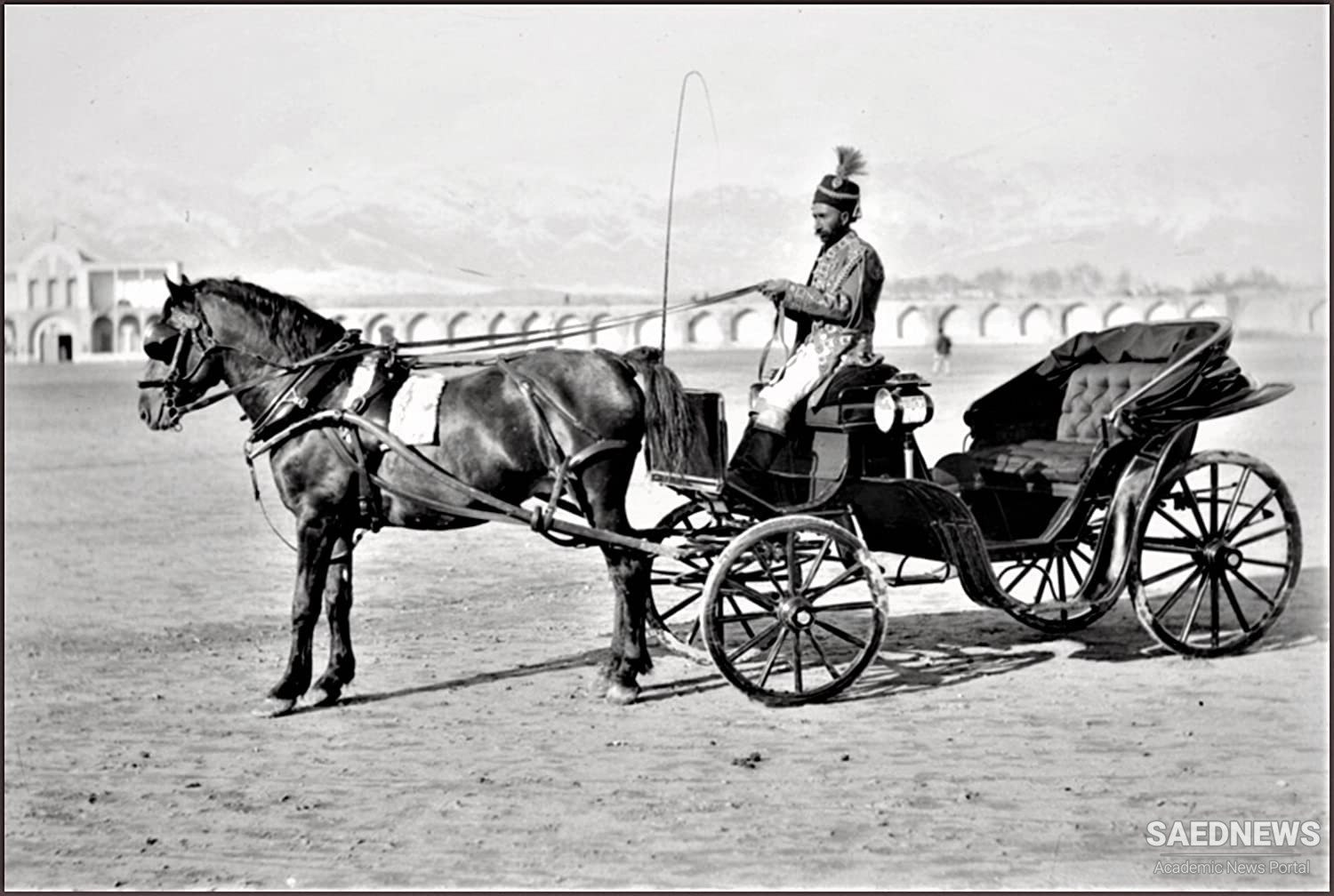

Even the Cossack Brigade, despite its royalist leanings, was mostly passive. In any event, its capacity to intervene had been weakened by its fi nancial problems. In addition, the unit’s 1,500 Iranian enlisted men were sympathetic to the popular demands for a national assembly and a constitution, especially aft er mullahs joined the protests. When the new commandant, a Colonel Liakhov, arrived in September 1906, he found that the brigade was out of the Russian offi cers’ control and was being run by a council of Iranian officers. Liakhov succeeded in abolishing the council and weeding out anti- Russian offi cers. He then gained the confi dence of his men by defending their interests, briefly improving the unit’s discipline and effi ciency. Nonetheless, popular resentment of the brigade caused the Russians to keep a lower profile.

Under mounting pressure, the ailing shah consented to the formation of a national assembly, called the Majles. One of Muzaff ar al- Din’s last offi cial public acts was to att end the inauguration of the new legislature in October 1906. The representatives of the First Majles, blurring their signifi cant diff erences in the interest of democratic unity, quickly drafted a constitution that arranged for sharing power with the court and set out the duties, limitations, and rights of the new government. The legislature also tried to pass legislation to create a strong army and curb the monarch’s power over the armed forces but failed. A dying Muzaffar al- Din fi nally consented to approve the constitution in December 1906, but it represented, at best, an uneasy truce between tradition and modernity.

Environmental Crisis and Revival of Spiritual Sensibilities

Environmental Crisis and Revival of Spiritual Sensibilities