A repertoire of melody types existed, for example, that was generated by an explicit “doctrine of figures” that created musical equivalents for the figures of speech in the art of rhetoric. Closely related to these “figures” are such examples of pictorial symbolism in which the composer writes, say, a rising scale to match words that speak of rising from the dead or a descending chromatic scale (depicting a howl of pain) to sorrowful words. Pictorial symbolism of this kind occurs only in connection with words—in vocal music and in chorale preludes, where the words of the chorale are in the listener’s mind. Number symbolism, another common device of the Baroque period, also is sometimes pictorial; in the St. Matthew Passion, for instance, it is reasonable that the question “Lord, is it I?” should be asked 11 times, once by each of the faithful disciples. The Baroque composer had at his disposal various other formulas for elaborating themes into complete compositions; skilled use of such formulas allowed the arias and choruses of a cantata to be spun out almost “automatically.” As a result of his intense activity in cantata production during his first three years in Leipzig, Bach had created a supply of church music to meet his future needs for the regular Sunday and feast day services. After 1726, therefore, he turned his attention to other projects. He did, however, produce the St. Matthew Passion in 1729, a work that inaugurated a renewed interest in the mid-1730s for vocal works on a larger scale than the cantata; the now-lost St. Mark Passion (1731); the Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248 (1734); and the Ascension Oratorio (Cantata No. 11, Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen; 1735). In 1726, after he had completed the bulk of his cantata production, Bach began to publish the clavier Partitas singly, with a collected edition in 1731. The second part of the Clavierübung, containing the Concerto in the Italian Style and the French Overture (Partita) in B Minor, appeared in 1735. The third part, consisting of the Organ Mass with the Prelude and Fugue [“St. Anne”] in E-flat Major (BWV 552), appeared in 1739. From c. 1729 to 1736 Bach was honorary musical director to Weissenfels; and, from 1729 to 1737 and again from 1739 for a year or two, he directed the Leipzig Collegium Musicum. For these concerts, he adapted some of his earlier concerti as harpsichord concerti, thus becoming one of the first composers—if not the very first—of concerti for keyboard instrument and orchestra. About 1733 Bach began to produce cantatas in honour of the elector of Saxony and his family, evidently with a view to the court appointment he secured in 1736; many of these secular movements were adapted to sacred words and reused in the Christmas Oratorio. The Kyrie and Gloria of the Mass in B Minor, written in 1733, were also dedicated to the elector, but the rest of the Mass was not put together until Bach’s last years. On his visits to Dresden, Bach had won the regard of the Russian envoy, Hermann Karl, Reichsgraf (count) von Keyserlingk, who commissioned the so-called Goldberg Variations; these were published as part four of the Clavierübung about 1742, and Book Two of Das Wohltemperierte Klavier seems to have been compiled about the same time. In addition, he wrote a few cantatas, revised some of his Weimar organ works, and published the so-called Schübler Chorale Preludes in or after 1746.

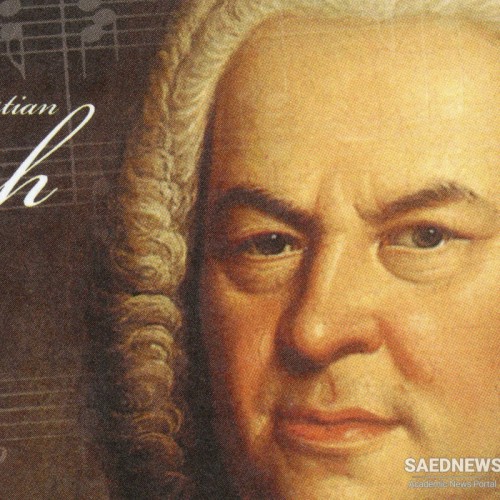

Johann Sebastian Bach the Organist-Composer

Johann Sebastian Bach the Organist-Composer