There he changed ships and reached a port in Mingrelia, intending to travel to Tiflis through that country and Imeritia. He describes the country and its unfortunate inhabitants, who were habitually sold to the Turks by their cruel masters. Of one beautiful slave Chardin writes: “She had incomparable Features in her Face, and a true Lily-white Complexion, and indeed I never saw more lovely Nipples, and a sounder Neck, nor a smoother Skin; which created at the same time both Envy and Compassion.”

Owing to disturbances caused by a Turkish raid, the traveller was advised not to land but, after some hesitation, he hired eight carts for his property and proceeded to a monastery, where he was received most hospitably by its head, Father Zampi. Upon news of his arrival with rich merchandise reaching the Court, the Princess of Mingrelia promptly visited the monastery and demanded to see his wares. Chardin attempted to pose as a friar but failed to deceive the Princess who, furious at his refusal to unpack his bales, said to Father Zampi: “You have both deceived me, but ’tis my Pleasure that the Newcomer say Mass before me.” Chardin, realising that trouble was imminent, buried or hid his most valuable effects and, scarcely had he done so, when the monastery was broken into by two nobles and their “assassinates.” They searched high and low, and Chardin describes how he threw two bundles worth £6000 into some thick bushes, and then suffered agonies while the robbers were searching the garden. At last the band departed, taking off some articles of small value, but Chardin could not find the precious bundles which were, however, finally recovered by a faithful servant.

Realising that he owed his escape to good luck and that his liberty, if not his life, was in danger, he hired a vessel and returned to Turkish territory. There he was fleeced to some extent by the authorities but, once inland, he travelled in perfect security and, crossing the Caucasus, arrived safely at Tiflis. At the capital of Georgia he was befriended by the Italian Capuchin monks and, through their devoted efforts, he was able to communicate with his comrade, whom he had left in charge of his property, and, after various narrow escapes from robbery, due to plots woven by a dismissed Moslem servant, he finally recovered his jewelry and money intact.

Thanks to the letters patent of the Shah and other recommendations from Persian Court officials, Chardin was welcomed warmly by the Prince of Georgia who also appreciated the handsome gifts he offered, which included “a large watch with a Lunary Motion and a Surgeon’s Case.” He appeared frequently at the Court and was consequently able to give an excellent account of the history of Georgia and of the manners and customs of the people. The most important festivity which he attended was the wedding of the Prince’s niece, and he notices that since Christian Georgia became subject to Persia, the women were kept apart from the men in the cities. The feast was gargantuan, the meat being served on silver dishes weighing five hundred ounces. There were three courses, each course “containing sixty of those large flat Dishes a piece.” Chardin describes as an expert the gold bowls, cups, horns, flagons and jugs. The quantity of wine that was drunk was enormous, the feast lasting until the morning, by which time everyone was dead drunk. The traveller comments : “Had I Drank as much as my Neighbours, I had dy’d upon the Spot: but the Prince had so much kindness as to give orders not to carry us any Healths.”

Shortly after this banquet, Chardin received permission to continue his journey. He was anxious to leave Tiffis, as the Prince pressed him to show him the jewelry he had brought for the Shah. This he naturally declined to do and, equally naturally, he felt uneasy as to what the autocratic Prince might do, especially as his reputation was far from good.

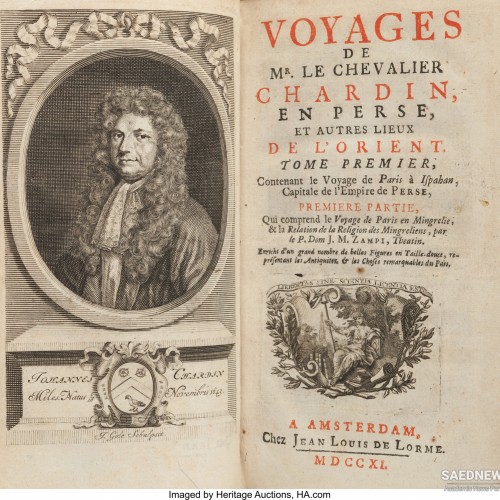

Jean Chardin's Travels in Persia

Jean Chardin's Travels in Persia