Adopting the term “Fundamental Law” also seems to have been inspired by the Fundamental Laws issued by Tsar Nicholas II, according to which the Duma was granted limited legislative powers but only with the ultimate endorsement of the tsar, who called himself the “supreme autocrat.” Similar tension between the Majles and the monarch was soon to emerge with the Iranian Constitutional Revolution.The members of the Electoral Law Committee adopted the term Fundamental Law in place of the French constitution so as to avoid conservatives’ accusations that they were adopting an alien institution contrary to Islamic shari‘a and the tradition of monarchy in Iran. Yet the secularizing agenda of the constitutionalists, boosted by dissident preachers and the burgeoning liberal press outside the Majles, was clear enough not to be missed by opponents, even though a handful of radical deputies led by likes of Hasan Taqizadeh, the celebrated deputy from Tabriz, did their best to camouflage their antiroyalist and anticlerical views. Fearing their opponents in the court and among conservative ulama, the Majles deputies soon realized that to avoid the fate of the Russian Duma—which was dissolved in July 1906 by order of the tsar—they had only a brief window of opportunity.

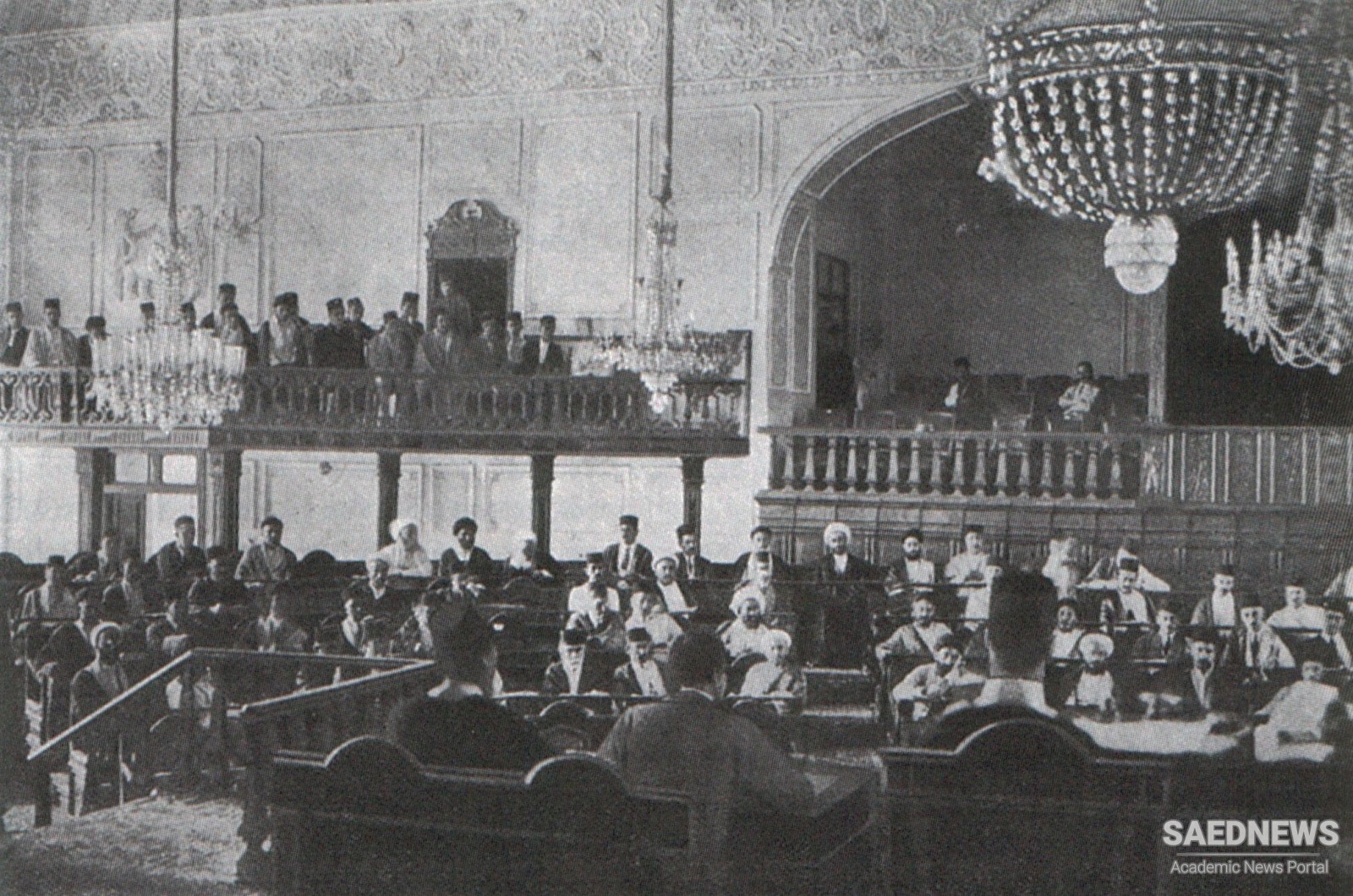

The Majles thus hastily drew up a document to be signed by the shah on December 30, 1906, on his deathbed. The Fundamental Law recognized the separation of three powers—with the Majles as the legislative body—far more than earlier demands for it to have a mere judicial function, and with the shah as the head of the executive. The news of the revolution stirred some interest not only nationally but in the European press as well. The shah died of kidney failure on January 3, 1907, and was immediately succeeded on the throne by his son, Mohammad ‘Ali Shah (r. 1907–1909), a man of decidedly different temperament and political orientation from his father.

It was remarkable enough that Iran had convened a parliament against all the odds. It was even more significant that the Majles not only framed a constitution but soon after, in October 1907, ratified a substantial document, the Supplement to the Fundamental Law. The latter document guaranteed basic liberties and laid the foundation for a constitutional system. This was achieved in an environment of growing tension with the court of Mohammad ‘Ali Shah and open hostility from the anticonstitutional clerical camp under Shaykh Fazlollah Nuri (1843–1909), who was allied with conservatives at the court.

Despite his early support for the constitutional movement, Nuri soon parted ways, posing a potent challenge to the Majles and the cause of constitutionalism. He coined the term mashru‘eh, obviously mimicking mashruteh, to imply that the shar’ (i.e., shari‘a), and not the shart (condition), ought to be the foundation of the new constitutional order. Though a prominent Usuli jurist, he did not articulate the meaning of mashru‘eh beyond generalities. Perhaps aware of the past Shi‘i jurists’ aversion to engaging in issues of political governance (which in the absence of the Imam of the Age considered any other form of worldly government to be categorically oppressive), Nuri remained in essence loyal to the theory of state-religion dual authority. Yet facing the reality of a modern legislature, he strove to find a role for the jurists, with himself at the helm. Not merely a judicial one but a role to enforce the shari‘a far beyond its accepted limits. He viewed the nascent Majles and its constitution as no more than a conspiracy hatched by heretics, Babis, and atheists, and he called on his clerical cohorts to oppose them. In his “rescripts” (lawayeh), periodically published from Shah ‘Abd al-‘Azim, where he had taken sanctuary, he attacked as non-Islamic such precepts as freedom of speech and equality before the law. Once the appeasing gestures by the Majles, including the inclusion in the constitution of a five-member mojtahed supervisory committee, appeared to be mere lip service to the ulama, Nuri quietly abandoned the idea of the mashur’eh and became a royalist supporting Mohammad ‘Ali Shah.

Growing Discontent and Aspiration of the Rule of Law: Emerging Constitutional Seeds

Growing Discontent and Aspiration of the Rule of Law: Emerging Constitutional Seeds