Local shrines were the focus for ceremonials celebrated by particular communities or occupational groups. Linking attachments to locality or occupation with affirmations of Shi’a commitment, and creating shared rituals, they were established and regular popular religious activities. The annual festival of the carpet craftsmen in the Kashan area, the flow of more or less affluent pilgrims to Mashad and Qum, the growth of village shrines like that at Sehkunj, near Kerman, with their opportunities for devotion, celebration and sociability or consolation, expressed that shared commitment and identity.

Central to collective devotion were the rituals associated with the martyrdom of Husein. The powerful legacy of this founding episode of resistance, suffering and conflict took various forms of collective commemoration. Rituals associated with these martyrs were conjointly undertaken by communities and preachers, reciters or ‘ulama. The major forms were mourning recitations recounting the Karbala events, and processions and dramas in the first ten days of Muharram.

The growth of these practices drew on popular organisation and ‘official’ sponsorship by ‘ulama and rulers. Over time rawzeh-khwani (mourning recitations) evolved into rituals performed in public, in specially designated venues (huseiniyehs, tekkiehs), and in private homes where individuals sponsored recitations and invited guests. Although specialists (rawzeh-khwans) provided recitations, rawzeh gatherings were organised and funded by pious individuals or groups, and involved active participation by those attending, who expressed their own involvement in the ‘Karbala narrative’ in response to the recitation.

The gazetteer of nineteenth-century Kerman spoke of rawzeh gatherings in caravanserais and private houses as well as in tekkiehs and madrasehs. Notables displaying piety among peers or clients, merchants and artisans celebrating the values central to their lives, and communities coming together in shared loyalty and grief for the Imams were agents rather than passive recipients of religious culture.

Similar developments shaped the mourning processions and ta’ziyeh (dramatic representations of the Karbala story) undertaken during Muharram. The processions involved groups of male believers moving through streets and public spaces, chanting and striking themselves with sticks, hands, blades or chains to commemorate Husein’s suffering. Ta’ziyeh performances combined traditions of public mourning and tales of the Karbala narrative in dramatised presentations of his martyrdom.

In the nineteenth century, both sponsors and performers of ta’ziyehs came from the communities where they took place, drawing large and responsive audiences ranging from elite visitors to tekkiehs established by rulers and notables to the participants at ta’ziyehs in humbler urban and rural settings. Merchants and others displayed piety and status by support for ta’ziyehs, or providing drinking water for participants in mourning processions (a practical contribution and a commemorative/symbolic reference to the denial of water to the Karbala martyrs).

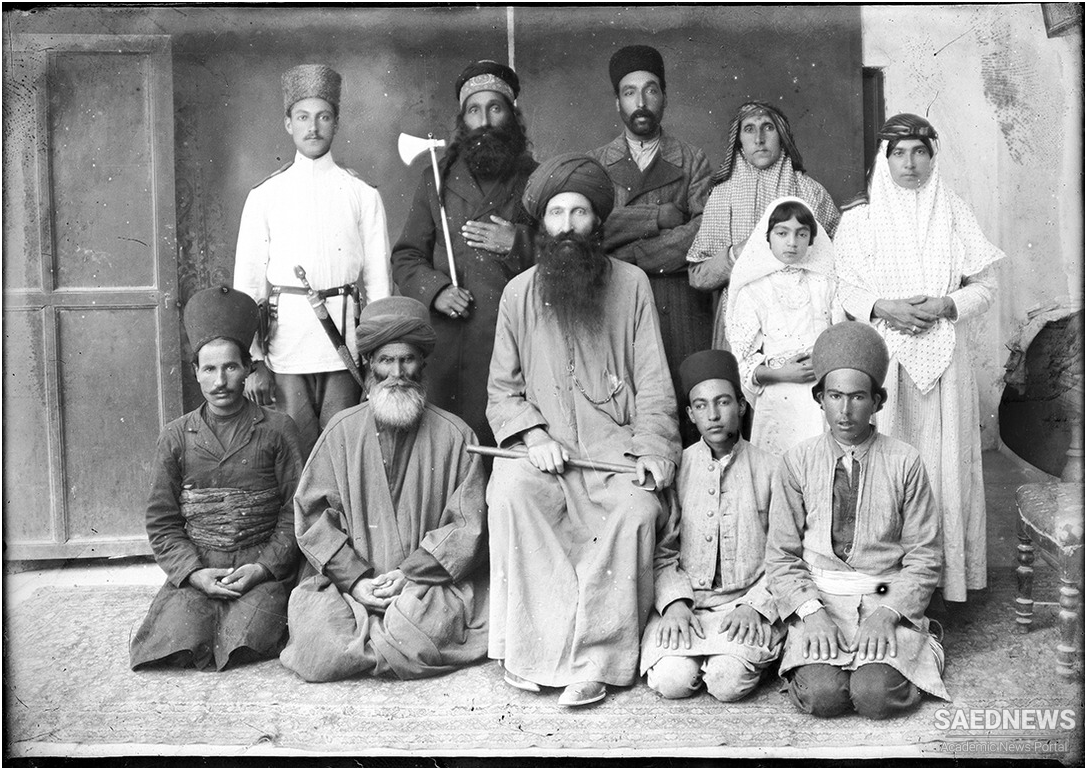

As with the rawzehs, processions and ta’ziyehs moved spectators to express their own responses. Such responses (cries, tears, gestures) were personal and collective in the sense that it was gathering as groups for ta’ziyehs and processions that stimulated individuals and gave their responses full significance. Active involvement of believers linked religious devotion, social solidarities and the meanings of the foundation narratives of Shi’ism. Early twentieth-century photographs and nineteenth-century drawings of rawzehs, Muharram processions, preaching and ta’ziyeh illustrate this.

They show specific groups (women, notables, mullas, servants) at an event, distinguished by dress and positioning. Written evidence similarly describes the collective presence of villagers and urban residents, the participation of specific subgroups, and shared involvement in these activities, noting how communal expressions of emotion contributed to the intensity of individuals’ reactions.

Iranian Family, Its Structure and Significance in Persian Culture

Iranian Family, Its Structure and Significance in Persian Culture