The skirmishes south of Tehran with the demoralized Cossack regiments headed by Russian officers and regular government troops were indecisive. Despite months of repeated Russian and British warnings that jointly and individually demanded that the nationalists stay away from the capital, a force of nearly three thousand Bakhtiyari and Gilan fighters engaged for two days in a mopping up operations inside the capital. Colonel Liakhov and his troops surrendered, only to be commissioned, ironically, back into service by the nationalists even though they momentarily faded out of the revolutionary limelight.

Mohammad ‘Ali Shah himself and an entourage of five hundred, including his hated army chief, Hosain Pasha Amir Bahador Jang, negotiated his way to the Russian legation, where he took refuge under the joint protection of the two powers. Conscious of European sensitivities, the nationalists quickly secured diplomatic missions and assured the safety of foreign residents, even before marching to the ruins of the Majles building, where on July 15 they officially announced the abdication of Mohammad ‘Ali Shah from the Qajar throne.

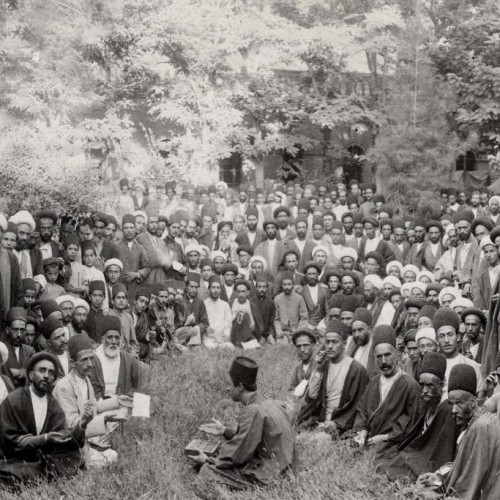

With a discipline that impressed even the mostly hostile European press corps, the Bakhtiyari tribesmen and a contingent of the Armenian fighters from Gilan restored order in the capital, set up a rudimentary headquarters, and soon declared Mohammad ‘Ali Shah’s minor son, Sultan Ahmad (1898–1930), as the new shah. The elder of the Qajar tribe, ‘Ali Reza ‘Azod al-Molk (1847–1910), became his regent. By any account, the success of the nationalist forces was impressive. There was no looting, revenge killing, or retaliation. Even more remarkable was the level of cooperation between the heterogeneous rank and file of Gilani and Bakhtiyari fighters, who could barely communicate with one another in Persian.

The conquest of Tehran was an ephemeral, but defining, moment in Iran’s modern history. Soon after the arrival of the Tabriz fighters and their heroes—Sattar Khan, now celebrated as Sardar Melli (national commander) and his colleague Baqer Khan as Salar Milli (national chief)—instilled a spirit of optimism in the hearts of many Iranians. Deposing Mohammad ‘Ali Shah and his mashru‘eh ally, despite Russia’s unabashed backing of the royalists, was a rare triumph in the age of high imperialism. For a moment, it seemed as if the desire to create a liberal democratic order had overcome not only the impediments of arbitrary rule and reactionary ulama, but also brutish European imperial ambitions. It was as though through a national struggle, and its narrative of salvation, the beast of misrule and misery had been subdued and a new road to prosperity paved. The new Ahmad Shah was hailed as a constitutional monarch, despite some talk of republicanism in the radical circles.

The nationalists’ maneuvering to power, and the level of independence their leaders displayed, took the representatives of Russia and Britain by surprise and generated much dismay. Russia had only complied with restoration of the constitution and abdication of the former shah with grudges, and Britain was not far behind. By the time Tehran was taken by the nationalists, at least three thousand Russian troops had already crossed the border and occupied northern Iran, stretching from Azarbaijan to Gilan and northern Khorasan and advancing as far south as Qazvin, only ninety-five miles from the capital.

The audacity with which imperial Russia trampled Iran’s sovereignty, contrary to the terms of the Anglo-Russian agreement ensuring the opposite, apparently required not even a diplomatic fig leaf. No longer shackled by a British counteraction, the Russian move had already cast its shadow over the newly restored but fragile regime. It also heightened anti-Russian sentiments that had been boiling up since the turn of the twentieth century. Iranians admired Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 and saw it as a promising sign that a European expansionist empire could be defied, if not defeated Earlier defeats of the British colonial army in the Second Anglo-Boer War, in 1902, stirred similar sentiments.

British Embassy the Sanctuary of the Constitutional Activists!

British Embassy the Sanctuary of the Constitutional Activists!