Of course these ancestors, especially Isma'Il, the founder of the state, had held radically different views of Shi'ism from the theologians who now triumphed as power slipped from the hands of a weak and irresolute ruler. These did not use their power to the best advantage of the country, any more than did their rivals inside the harem, who with few exceptions were men of little ability.

The decline in royal power, the indifference of the shah with regard to the affairs of state, his lack of initiative, energy and consistency ruled out all possibility of progress in the country, whether one considers trade and commerce, administration or agriculture, the national finances or the army. Nor were successes in foreign policy to be achieved in the prevailing circumstances. Nevertheless, the institutions of state continued to function, even if ominous signs of ossification and torpor became noticeable, for example, in the military sphere.

Even cultural life continued on its way, in some fields with considerable achievements. Examples of craftwork, such as ceramics, metalwork and textiles, testify to the uninterrupted activity at the monarch's court workshops. Their products nowadays enjoy immense popularity amongst collectors and museums throughout the world. Architecture, too, remained productive. The shah was reponsible for the improvement and extension of his palace buildings and the Madrasa-yi Chaharbagh, founded by his mother, is even one of the masterpieces of Safavid architecture.

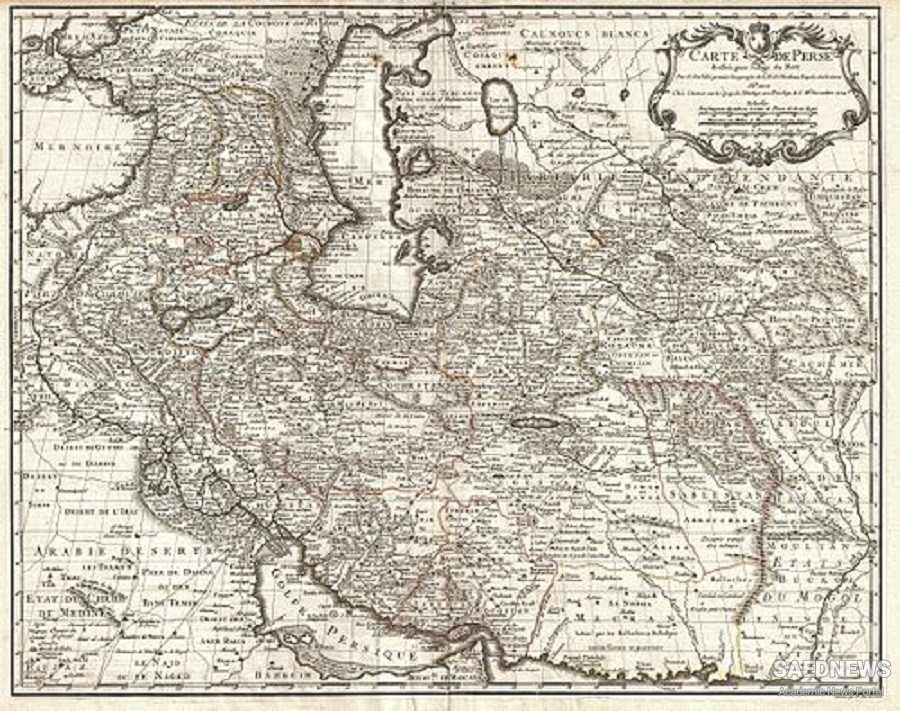

Contacts with Europe continued: we learn of legations from the courts of Louis XIV and Peter the Great in 1708, as well as a further legation from the Tsar in 1715. Persia herself sent diplomatic missions, for example to France. Although these exchanges were concerned primarily with specific problems of international trade, they were at the same time not without significance for the cultural and particularly the artistic development of the country. They brought aesthetic ideas from the West to Persia, European works of art such as paintings and even Western artists and craftsmen.

Thus the already mentioned European influence on Persian art, especially painting, was enhanced. Clearly the shah himself did not stand in the way of this development, since he even agreed to pose for a Dutch portrait painter. In this respect, at any rate, he had no religious scruples.

Safavids after Shah Safi's Death

Safavids after Shah Safi's Death