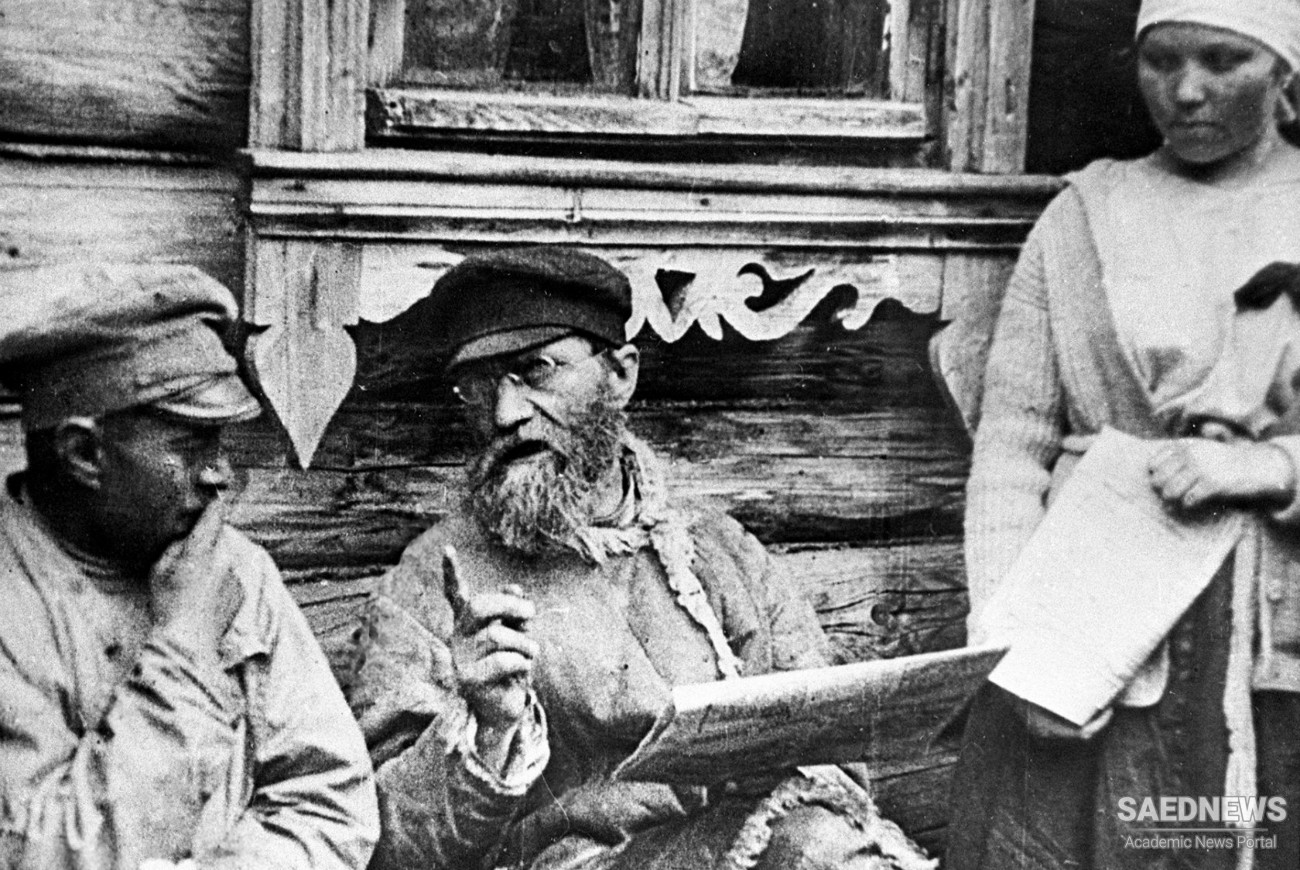

From the start, governments had a strong stake in folk music. The regulation of working instrumentalists goes back to medieval and Renaissance times in Europe, as a way for city fathers to control celebrations and the activities of a potentially dangerous class of citizens. Still, in remote parts of Norway, “plenty of fi ddling went on that was not for pay, and thus was not subject to regulation . . . certain venues were diffi cult or impossible to keep under offi cial control,” such as “the regional markets” where “fiddlers met and exchanged tunes.”

The growth of the nation-state only intensifi ed the urge to regulate folk music, coupled with the need to support local traditions. In other words, the offi cial managers of music have tried both carrots and sticks to this end. From promoting internal cohesion through stimulating exportable culture, planners and promoters have worked from the top down to create bottom-up change, circulation, and control. Whether for monarchist, socialist, or democratic agendas, bureaucrats have taken charge of what is supported, allowed, and sent abroad. Eventually, mainly in the United States, academic patrons and gatekeepers took on some of these functions, in the name of education and enlightenment. But first came the state, as early as the late 1800s, across Europe, from Britain to the Balkans, channeling offi cial energy through school systems, songbooks, and sponsored singing societies.

The most fl amboyant, and maybe the most studied, chapter of this history unfolded under socialism, from 1917 to 1991 in the Soviet Union, and from around 1949 to 1989 in central and southeastern Europe, and still today, to some extent, in China, Vietnam, Cuba, and North Korea. Bureaucrats located folk music at the intense intersection of ideology and nationalism. What better way to justify Bulgarian or Romanian state control than to see it as the will of a singing and strumming “people” of single purpose and identity?

Donna Buchanan summarizes the situation in Bulgaria as she unpacks the offi cial term narodno, based on a Slavic root that can translate into English as both “national” and “folk”: “Because it collapses the folk or traditional, ethnic, national, and people’s into a single construct, narodno lent a sense of historicity and hence legitimacy to post-1944 socialist customs, whether we consider the bestowal of the federal award title Naroden Artist (People’s Artist) or the signifi cance of narodni ensemble (folk ensembles).” The chain of command that linked villages to the capital cities in these societies was so intricately braided that no simple flowchart can describe its strands adequately. Talented village musicians were brought to town to undergo professional formation, which reshaped their sense of self. They “became travelers, physically and intellectually, circulating fl uidly amongst hamlets, municipalities and transcontinental megalopolises” as the government built folk music into an export industry.

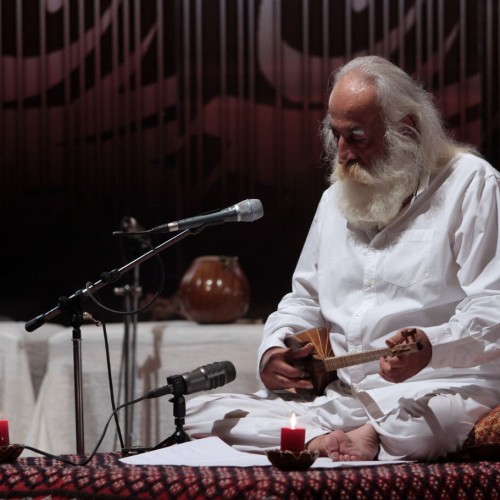

The Rhythmic Makeup of Gusheh in Classic Persian Music

The Rhythmic Makeup of Gusheh in Classic Persian Music