And a series of teaching manuals was compiled by Ruhollah Khaleqi for use in his newly founded Conservatory of National Music. Several other teachers in Tehran have also written manuals for their particular instruments. The most widely used publications are the works of Abol Hassan Saba (d. 1957). Three versions of his radif have been published, one for violin, one for santur, and one for tar and sehtar. In contrast to examples from theory books, the pieces in these teaching manuals, especially those in the Saba books, are remarkably close to performance practice. Each of these pieces could be regarded as a finished composition, and they are often performed quite literally by younger musicians.

Of the few transcriptions of the entire radif, that is, those containing several hundred pieces, the first was that of the statesman and amateur musician Mehdi Gholi Hedayat. A former prime minister of Iran and also a student of Mirza Abdullah, Hedayat spent seven years transcribing the radif as played to him by the physician Montazem al-Hokama. This manuscript version of the radif, dated 1928, is now in the library of the Conservatory of National Music.

The radif of Mussa Maruífi, which has official sanction, is also significant for its accessibility. More than one thousand copies were printed in 1963, and the Ministry of Art and Culture plans several more editions. Having reached the music libraries of many universities in the United States and Europe, this is likely to be the single most influential transcription of the radif for students in Iran and abroad.

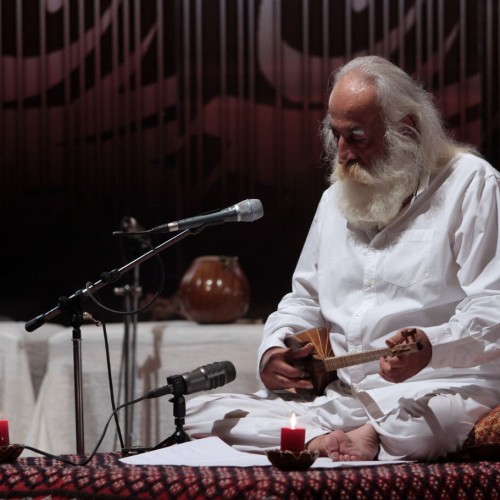

A final source, not directly quoted but used as a guide in selecting the examples that follow, is oral tradition as transmitted through live performances. Among the musicians whose performances were used are Ahmad Ebadi, Nur Ali Borumand, Khatereh Parvaneh, Mohammad Heydari, Faromarz Payvar, Kassayi, Hossein Malek, Hushang Zarif, and Banan. Tape recordings and transcriptions prepared by the author and by Genc ichi Tsuge were also used for this purpose.

The melodies quoted for each dastgah are those of its first gusheh, the daramad. This gusheh, which determines the name as well as much of the character of the entire dastgah, may be considered the single most important melody in the dastgah. The initial gusheh, however, does not represent the dastgah completely,· for one important characteristic of each dastgah is its entire system of gusheh-ha. But, within the scope of this present study, it was judged preferable to consider only one gusheh from each dastgah in broader detail, mentioning some of the other gusheh-ha only briefly. For each of the twelve dastgah systems, at least four musical examples will be given to illustrate the daramad, two from the theoretical literature and two from a literature closer to musical practice. The briefest and most explicit musical quotations are from the theory books. Of these, two versions will be presented in order to show variation in the melody acceptable even between two musicians as close as master and disciple. The first in each case is by Ali Naqi Vaziri; the second, by his pupil and close associate, Ruhollah Khaleqi. The third example for each dastgah is taken from one of the radif-ha of Abol Hassan Saba, selected because his are the most popular teaching manuals in Tehran today and are close to what is actually performed by contemporary musicians. The fourth example, the one most like an improvised performance in a traditional manner, is that from the Mac ruffi radif. Finally, for a few dastgah-ha, additional examples of special interest are presented.

The Rhythmic Makeup of Gusheh in Classic Persian Music

The Rhythmic Makeup of Gusheh in Classic Persian Music