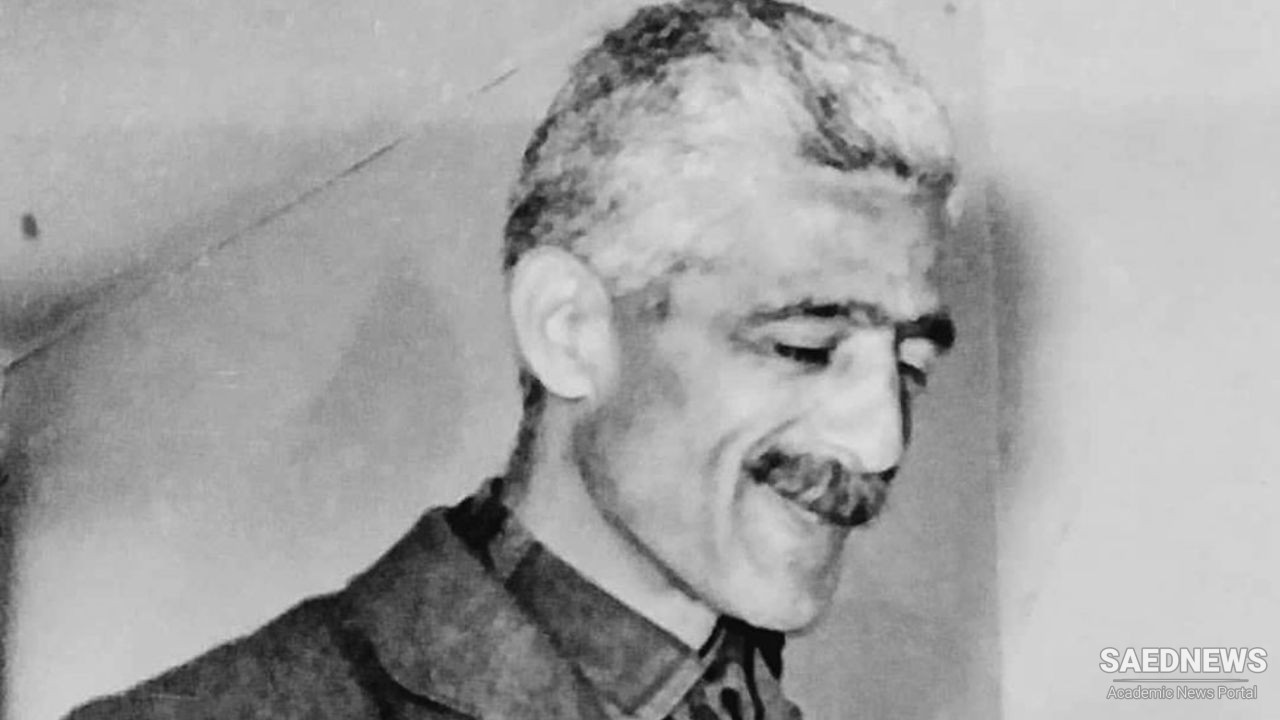

The 1920s was a decade of some fundamental changes in Iran, as Reza Shah established his autocratic rule at the expense of both the remnants of the defunct Qajar aristocracy and the relatively deactivated and subdued clerics. While the old Qajar aristocrats, stripped of their claims to nobility, competed for the lucrative bureaucratic posts in the new regime, a conservative and apolitical generation of clerics, headed by the distinguished resuscitator of the Qom scholastic seminary, Ayatollah Ha'eri, was putting to rest the tumultuous memories of the Constitutional period. Although the rule of Reza Shah in the 1920s increasingly curtailed the public and political domains of the Shia clerics, the latter continued to receive communal respect in the immediate context of their lives. Al-e Ahmad's grandfather, Sayyid Taqi Taleqani, was a locally prominent and respected cleric who led the public prayer at his local mosque in Tehran. Deeply revered and honored, Sayyid Taqi Taleqani would attract crowds of well-wishers who would seek to kiss his hands and pay their respects when they spotted him on his way to the mosque. Al-e Ahmad's father, Ahmad, the first son of Sayyid Taqi Taleqani, was an equally respected cleric who followed in his father's footsteps in religious piety and practice. Much of Al-e Ahmad's childhood in the 1920s and his adolescence in the 1930s was spent in the shadow of his religious family. His father obviously wore the religious habit. So did Jalal Al-e Ahmad himself, up to and including his final high school years in the early 1940s. Wearing the religious habit in those days was more than merely an identification with Islam and the clerical order. It had been turned into a political statement. When, in 1928, Reza Shah restricted the use of the clerical habit, in the hope of substituting the tie and chapeau for the turban and aba, the measure caused much resentment in many religious circles. The young turbaned and robed Al-e Ahmad must have felt particularly antagonized by Reza Shah's determination to give his Iranian subjects a European look. The effects of these antagonisms would later surface in Al-e Ahmad's Gharbzadegi (Westoxication), his most powerful indictment of blind "Westernization." At the time, however, wearing of the religious habit was a particularly isolating factor, going against, as it were, the tide of the time. Al-e Ahmad grew up with an exacting and demanding father whose religiosity had been aggravated by a society assuming an increasingly secular bend and by an absolutist tyrant determined to hasten the implementation of that secularism. In 1929 Reza Shah banned Muharram ceremonies, the annual commemoration of the death of al-Husayn, the third Shii* Imam, in 628 C.E. Such policies greatly dismayed Al-e Ahmad's father. The six-yearold Al-e Ahmad's experience of the annual ceremony was thus partially curtailed by the abrupt cessation. In 1936 Reza Shah ordered the unveiling of Iranian women. This would greatly aggravate Al-e Ahmad's father. The lives of the young Al-e Ahmad's female relatives became much more restricted. Al-e Ahmad, in particular, felt the moral pressure of a father whose frustrations with society at large spelled ethical absolutism for his own household. Under the imposing shadow of two mutually exclusive father figuresone his own, the other Reza ShahAl-e Ahmad was raised with paradoxical demands upon his character. These dual demands, aggravated in their intensity by being mutually exclusive and yet juxtaposed, pulled the young Al-e Ahmad in two diametrically opposed directions: one, the faith and practices of his biological father and ancestry, representing the old Persia; the other, the ideology and policies of an autocratic patriarch, forging the new Iran. Although later in life Al-e Ahmad would adopt a series of ideological stands fundamentally opposed to those of Reza Shah and his successor, Mohammad Reza Shah, the innate opposition between the authority of his own father, representing the old Shii Persia, and the father figure of a changing world, promising a new secular Iran, would remain with him permanently. Westoxication, his most celebrated contribution to modern Iranian political culture, is a crucial battlefield for this lifelong paradox.

Modernization, Rule of Law and Formation of Civil Society in the Age of Nasir al-Din Shah

Modernization, Rule of Law and Formation of Civil Society in the Age of Nasir al-Din Shah